Category: Japan’s electronics multinationals

-

SoftBank acquires ARM Holdings plc: paradigm shift to internet of things (IoT) and a Vodafone angle

On 18 July 2016 SoftBank announced to acquire ARM Holdings plc for £17 per share, corresponding to £24.0 billion (US$ 31.4 billion) SoftBank acquires ARM: acquisition completed on 5 September 2016, following 10 years of “unreciprocated love” for ARM On 18 July 2016 SoftBank announced a “Strategic Agreement”, that SoftBank plans to acquire ARM Holdings…

-

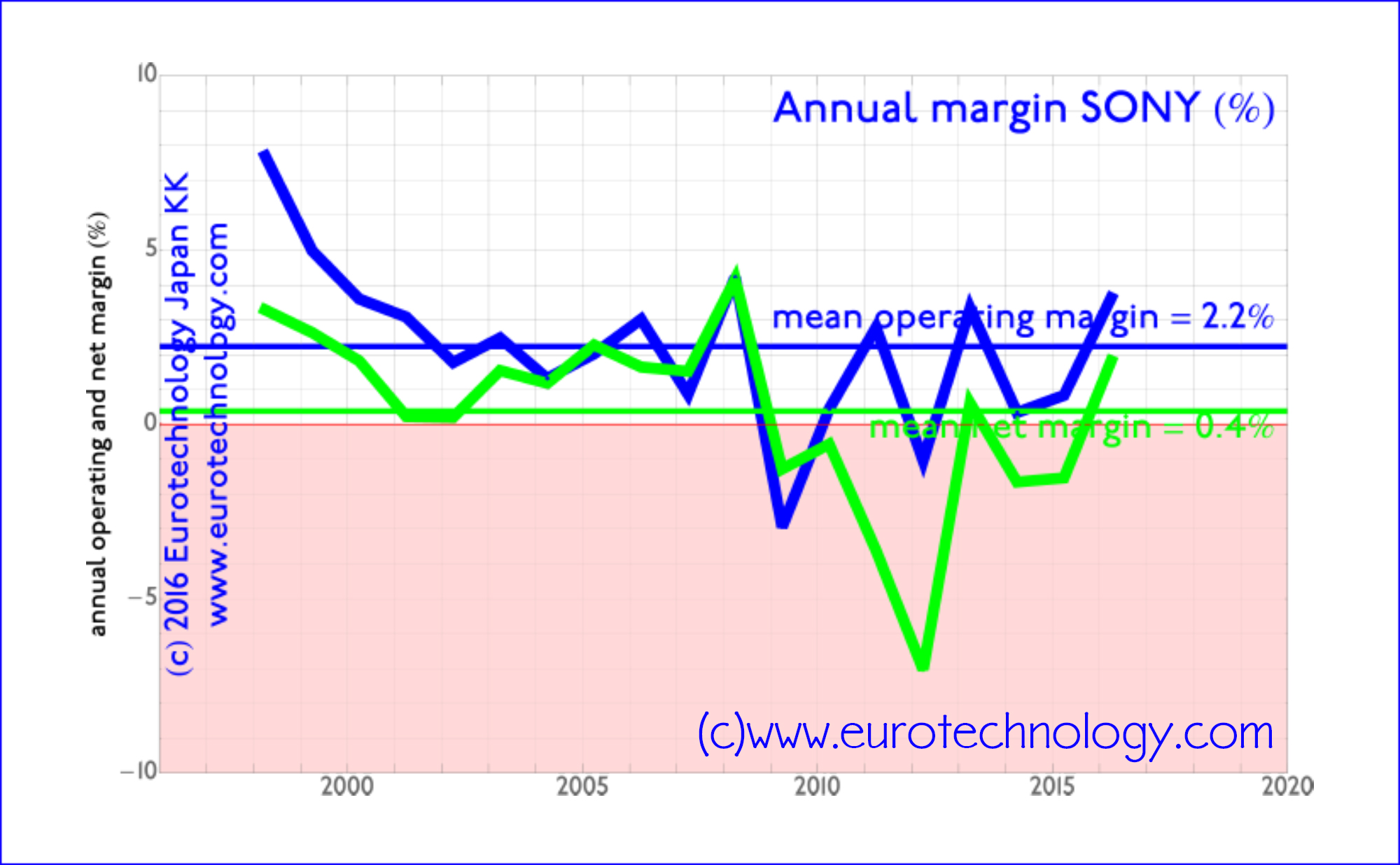

SONY 70th Birthday: Happy Birthday SONY!

Today: by far the strongest profits are not from electronics or Playstation, but from the subsidiary SONY Financial Holdings Inc within Japan SONY 70th Birthday: Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (Totsuko) was founded on May 7, 1946 SONY celebrates 70th Birthday today – SONY’s predecessor Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (東京通信工業株式会社), Totsuko (東通工) was founded on May 7, 1946…

-

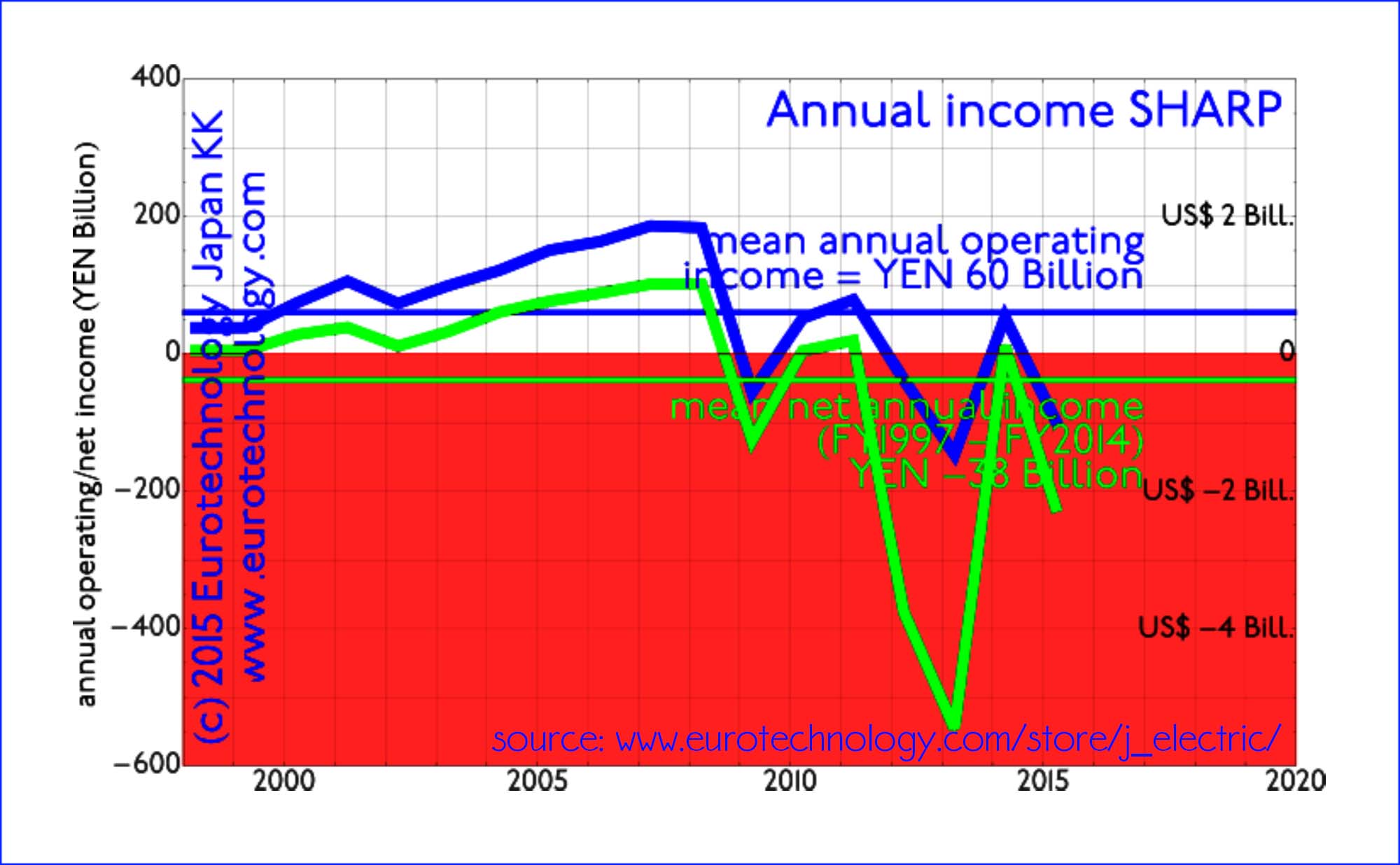

SHARP and the future of Japan’s electronics

SHARP is in the news, but its about Japan’s US$ 600 billion electronics sector The need for focus and active portfolio management SHARP, supplier of displays to Apple, faces repayment of about YEN 510 billion (US$ 4.2 billion) in March. Innovation Network Corporation of Japan INCJ (産業革新機構) and Taiwan’s Honhai Precision Engineering (鴻海精密工業) “Foxconn” compete…

-

Economic growth for Japan? A New Year 2016 preview

Economic growth for Japan in 2016? Economic growth: Almost everyone agrees that economic growth is preferred over stagnation and decline. Fiscal policy and printing money unfortunately can’t deliver growth. Building fresh new successful companies, returning stagnating or failed established companies back to growth (see: “Speed is like fresh food” by JVC-Kenwood Chairman Kawahara), and adjusting…

-

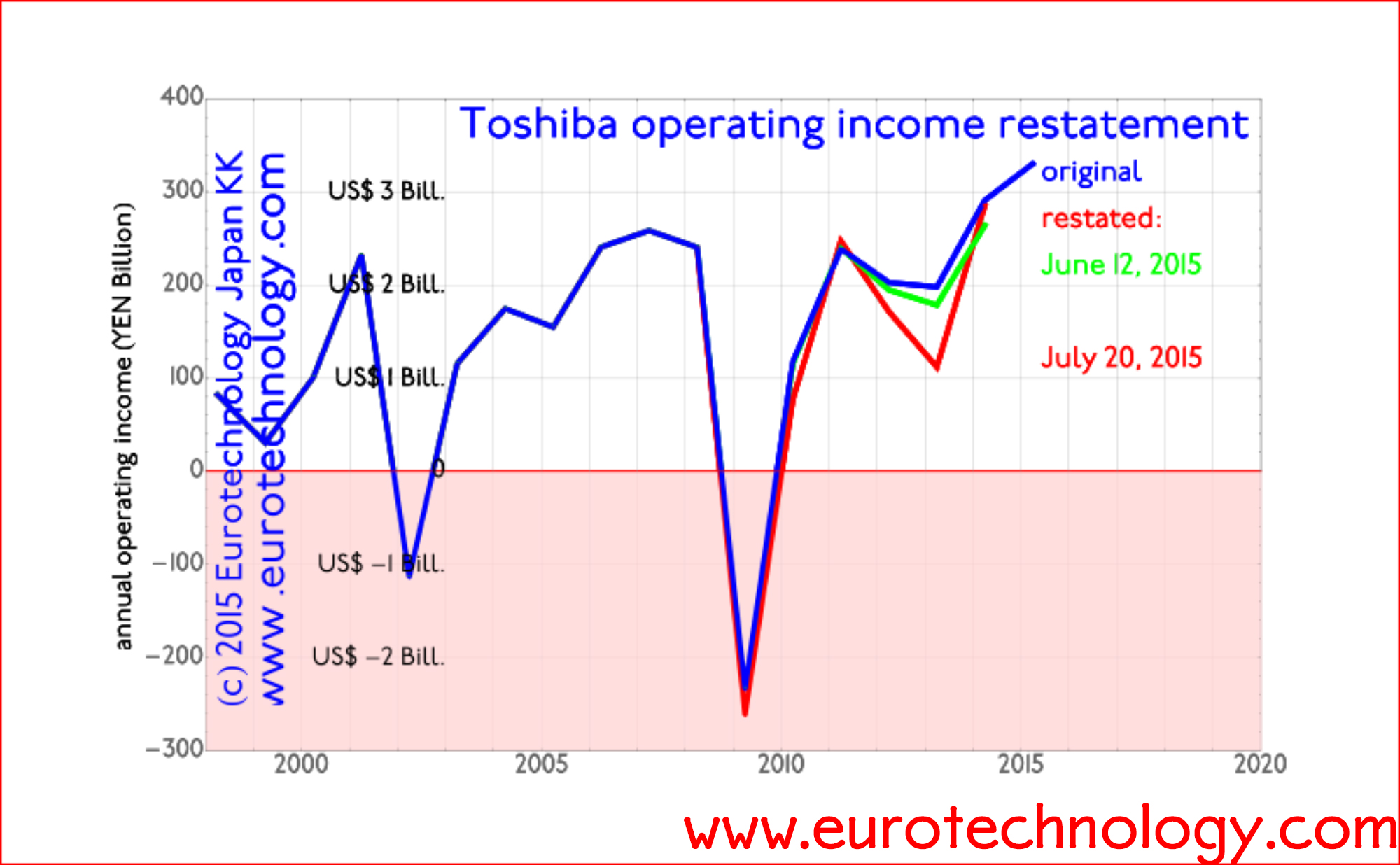

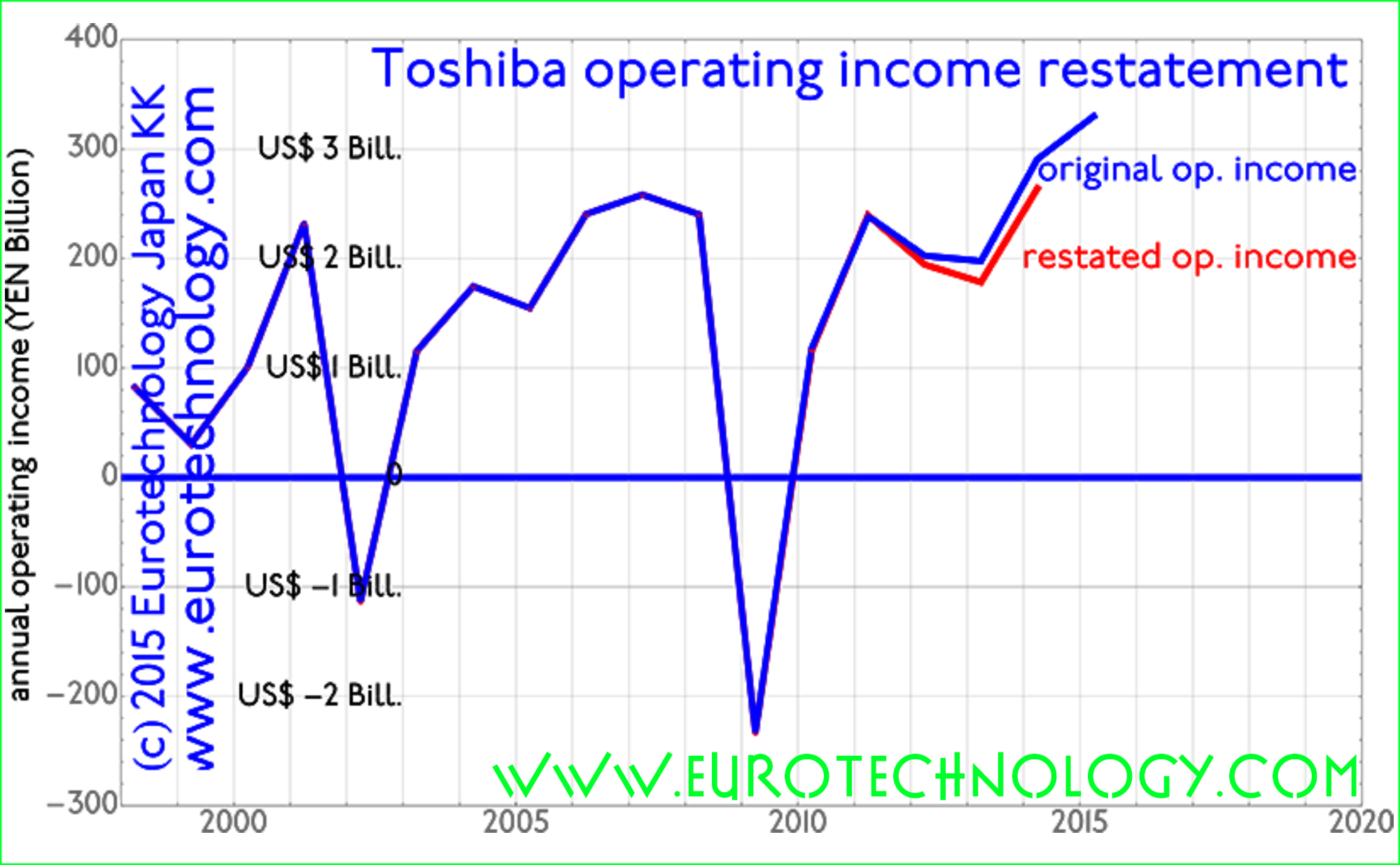

Toshiba income restatement: corresponds to one full year of average operating income

Toshiba’s income restatement announced by the independent 3rd party committee by Gerhard Fasol Independent 3rd party committee chaired by former Chief Prosecutor of Tokyo High Court On 12 June, 2015, Toshiba announced corrections to income reports, and at the same time engaged an independent 3rd party investigation committee headed by former Chief Prosecutor at the…

-

Toshiba accounting restatements in context

July 21, 2015: Update – report of the independent 3rd party committee chaired by former Chief Prosecutor of the Tokyo High Court. Corrections amount to 2 1/2 years (31.5 months) of average annual net profits by Gerhard Fasol Sales stagnation combined with almost zero net profit of Japan’s top 8 electronics companies creates increasing pressure…

-

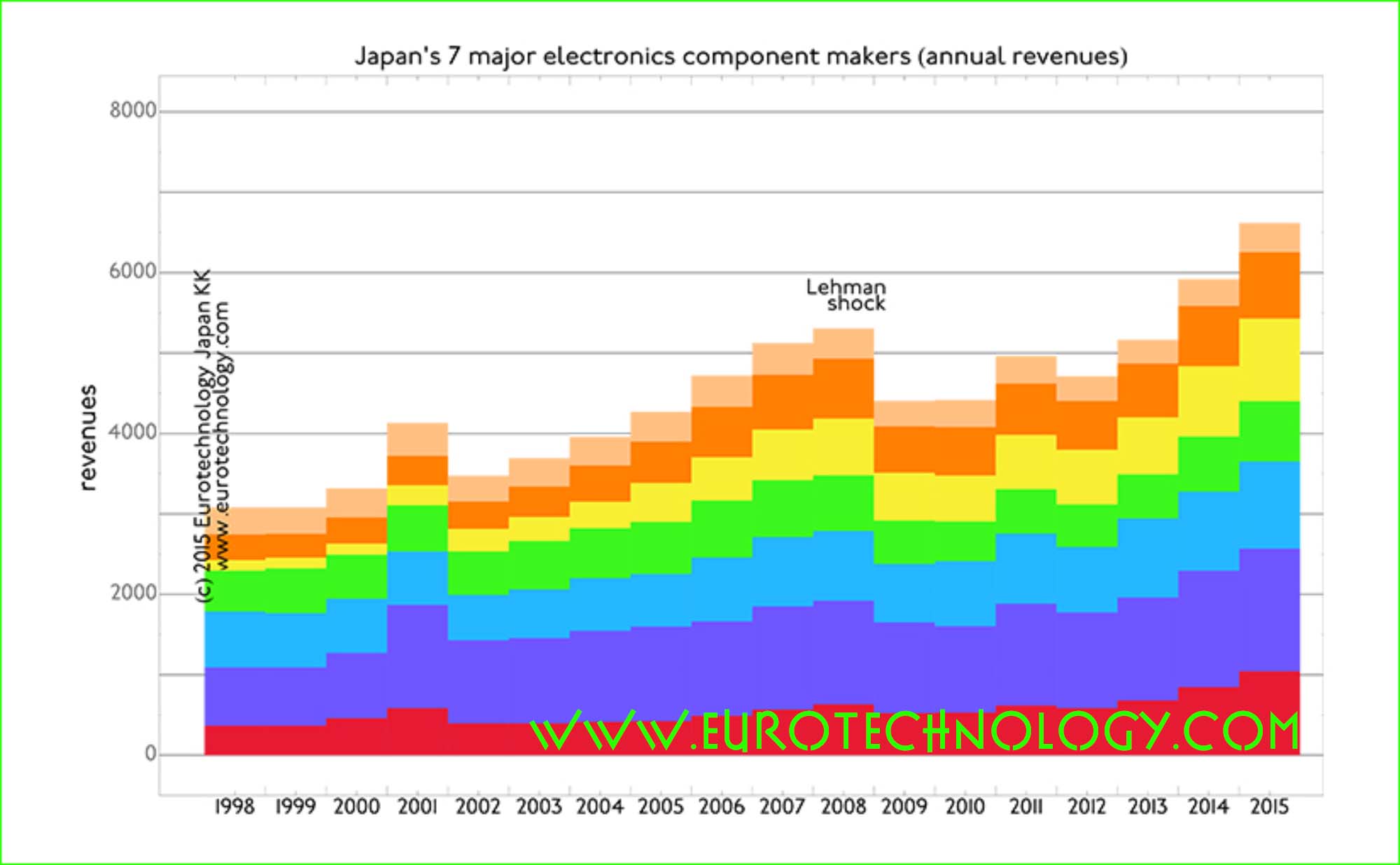

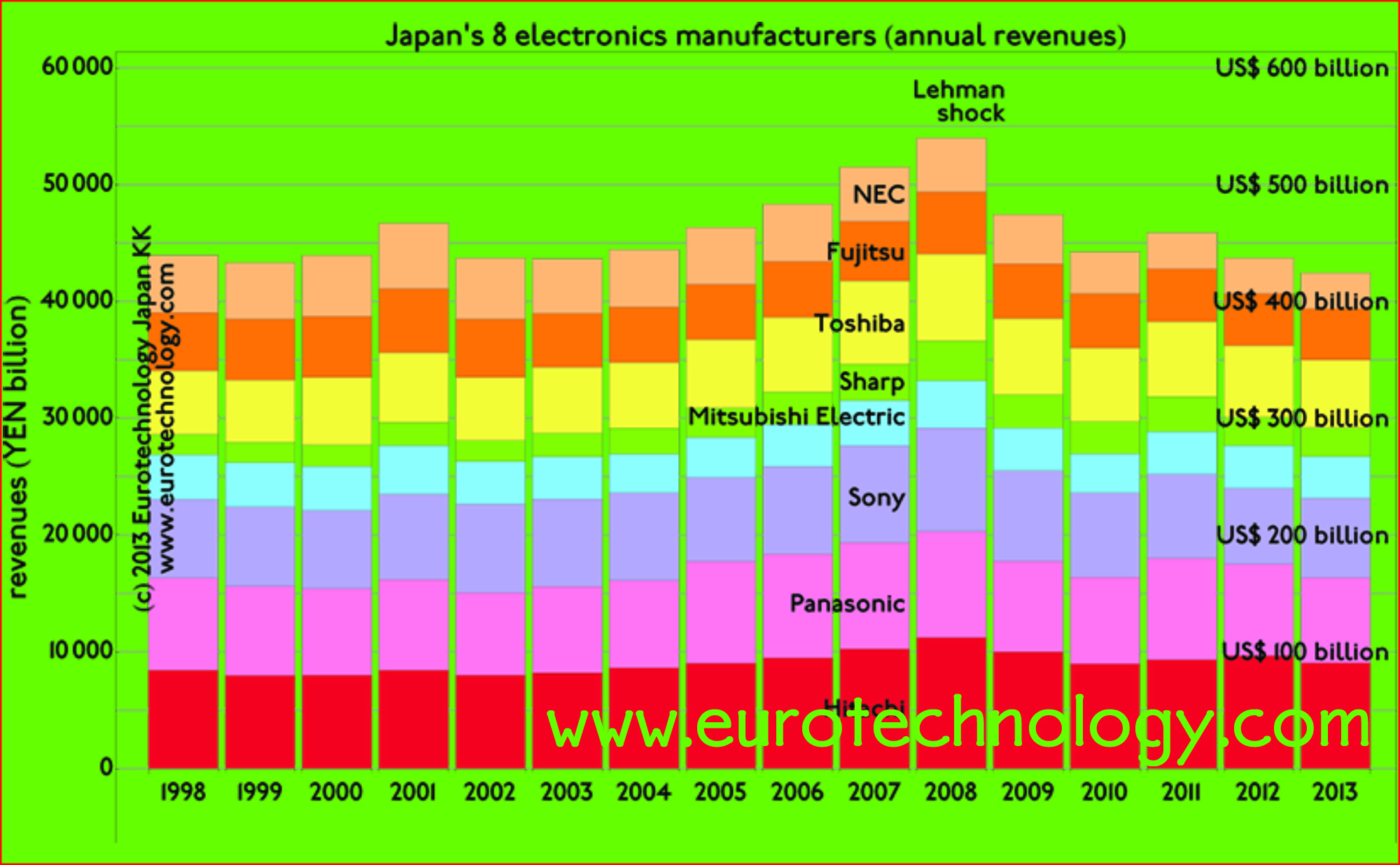

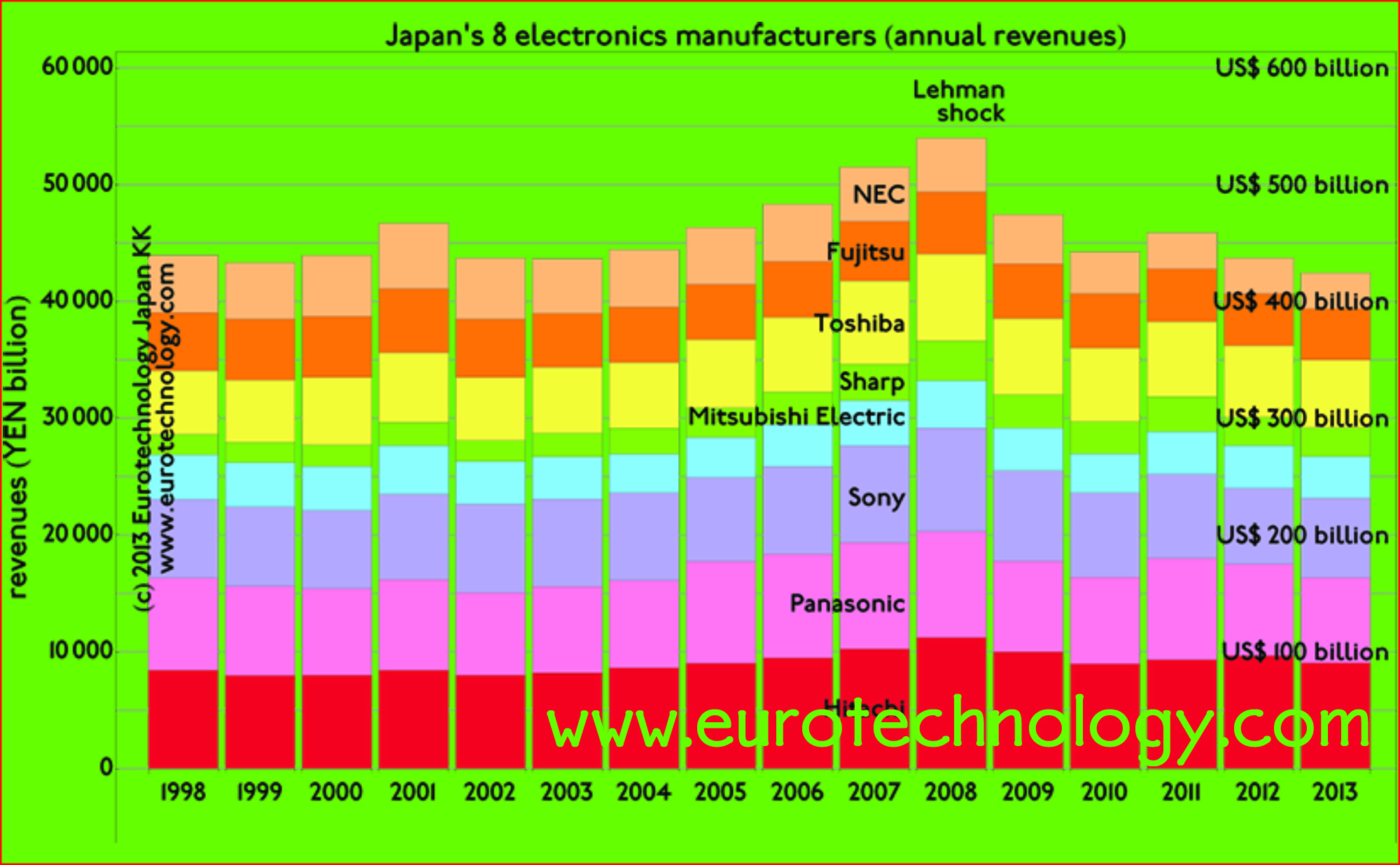

Japanese electronics parts makers grow, while Japan’s iconic electronics makers stagnate

by Gerhard Fasol Japan’s iconic electronics groups combined are of similar size as the economy of The Netherlands Parts makers’ sales may overtake iconic electronics groups in the near future – they have already in terms of profits In our analysis of Japan’s electronic industries we compare the top 8 iconic electronics groups with top…

-

Japan Exchange Group CEO Atsushi Saito: proud of Corporate Governance achievements, but ashamed of Toshiba

New Dimensions of Japanese Financial Market Only with freedom and democracy, the values of open society and professionalism can the investment chain function effectively The iconic leader of the Tokyo Stock Exchange since 2007, now Group CEO of the Japan Exchange Group gave a Press Conference at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan on June…

-

Sir Stephen Gomersall: Globalization and the art of tea

by Hitachi Chief Executive for Europe and subsequently Hitachi Board Director (2004-2014) Sir Stephen Gomersall: Princess Chichibu Memorial Lecture to the Japan British Society at Ueno Gakuen, Tokyo, 5 March 2015 Sir Stephen Gomersall: It is a great honour to be giving this lecture this evening. HIH Princess Chichibu was a charming and broad-minded Patron…

-

Steve Jobs and SONY: why do Steven Jobs and SONY reach opposite answers to the same question: what to do with history?

Steve Jobs and SONY: why 180 degrees opposite decisions? Steve Jobs donates history to Stanford University in order to focus on the future Steve Jobs and SONY – when Steve Jobs when returned to Apple in 1996, and now SONY are faced with the same question: what to do about corporate archives and the corporate…

-

TowerJazz to acquire three of Panasonic’s semiconductor fabs (Nikkei headline)

TowerJazz acquires three of Panasonic’s large written off wafer fabs for around US$ 100 million Massive market entry to Japan for TowerJazz Nikkei (the world’s biggest business daily, see our J-Media report) reported as their top headline yesterday, that TowerJazz is planning to acquire interests in three of Panasonic’s reportedly largely written-off semiconductor fabs valued…

-

Japan electronics industry seen by Freescale-Japan President & “Asian Le Mans Race” at Fuji Speedway

David Uze, President for Japan & Korea of Freescale on Japan electronics industry Perspectives for electronics industries in Japan 【日本語版こちらへ】 In this newsletter David Uze, President for Japan & Korea of the global semiconductor electronics company Freescale, shares his success story in Japan, and his perspectives on Japan’s electronics industry sector…. note: compare also with…

-

NEC revenues shrink from YEN 5000 billion in 1998 to YEN 3000 billion in 2012

NEC is one of NTT’s traditional four equipment suppliers NEC is one of NTT’s traditional suppliers of telecom equipment, and one of Japan’s flagship electronics companies. In the early days of the PC age, NEC dominated Japan’s PC market with the 98 series of PC, which had a NEC-proprietary variation of MicroSoft’s MS-DOS operating system.…

-

NEC smartphone termination, discussions with Lenovo failed

NEC smartphone – admits losing against competition from Apple and Samsung NEC smartphone – NEC used to be No. 1 in Japan’s “Galapagos keitai” market Just a few years ago, NEC was No. 1 in market share of Japanese pre-smart phone “Galake” (Galapagos-keitai, for a review of Japan’s Galapagos effect click here) super-feature phones. Recently…

-

Sony earnings boosted by weak yen – BBC interview about SONY earning results

Helped BBC with the article “Sony earnings boosted by weak yen and smartphone sales“ https://www.bbc.com/news/business-23527714 for detailed analysis of Japan’s electronics industry sector including SONY, see: Copyright 2013 Eurotechnology Japan KK All Rights Reserved

-

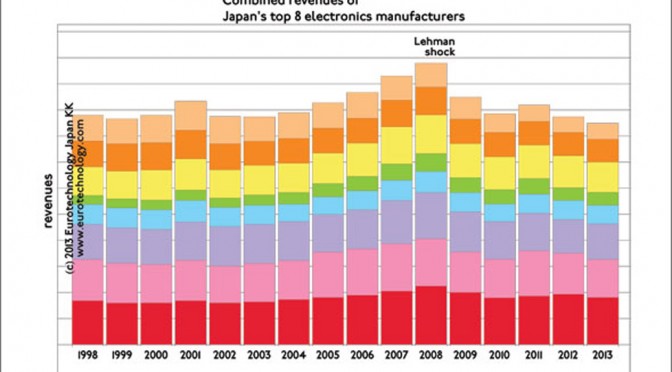

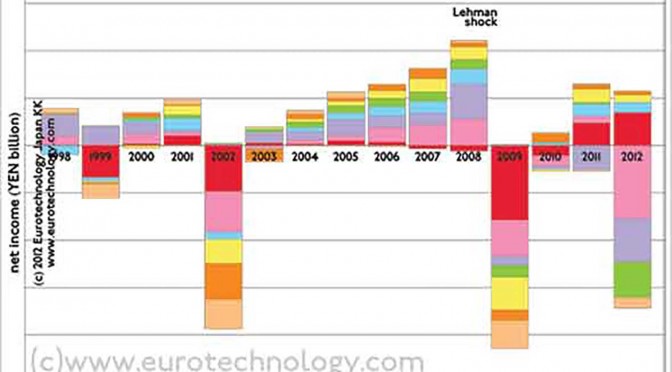

Japan’s electronics giants – FY2012 results announced. 17 years of no growth and no profits.

Japan’s electronics giants: as large as the economy of Holland, but 17 years of stagnation. No growth & no profits. Daniel Loeb: SONY’s uninvited guest gives Japan’s business culture a jolt Japan’s electronics giants combined are as large as the economy of Holland, but did not grow for about 17 years, and on average lost…

-

SONY results for FY2012 (ended March 31, 2013)

SONY’s first profits in 4 years come from selling assets and buildings SONY results for FY2012- BBC interview SONY announced annual financial results today, and BBC interviewed me twice to comment on the results (read comments here on the BBC website). After 4 years of net losses, it is comforting to see SONY report profits…

-

Intellectual Japan – BBC: “Japan has to become a brain country” – from mono zukuri to brain country

Intellectual Japan: Japan’s electronics companies need new business models – interview for the BBC The BBC recently examined why Japan’s electronics sector has to create new business models, and quotes “Japan has to become a brain country”. Japan’s top 8 electronics companies combined are as large as the Netherlands economically, but have shown zero growth…

-

SONY profits: 56% of profits are from selling life insurance and financial products (manuscript invited by BBC)

Games are 11% of SONY’s sales SONY profits: Currently 56% of SONY’s profits come from selling life insurance and financial products Games are 11% of SONY‘s sales – and currently 56% of SONY profits come from selling life insurance, consumer loans and financial products in Japan. Games are important, but are not going to make…

-

Kazuo Inamori, founder of Kyocera and DDI (KDDI), rebuilds Japan Airlines using Amoeba Management (アメーバ経営)

Kazuo Inamori (稲盛 和夫) one of Japan’s legendary serial entrepreneurs Japan Airlines (日本航空株式会社) turnaround from bankruptcy Bad news from Japan’s electronics industry sector makes global headlines this week (I was interviewed on BBC, US National Public Radio etc) – in this newsletter, lets look at some good news from Japan. Kazuo Inamori (80 years old,…

-

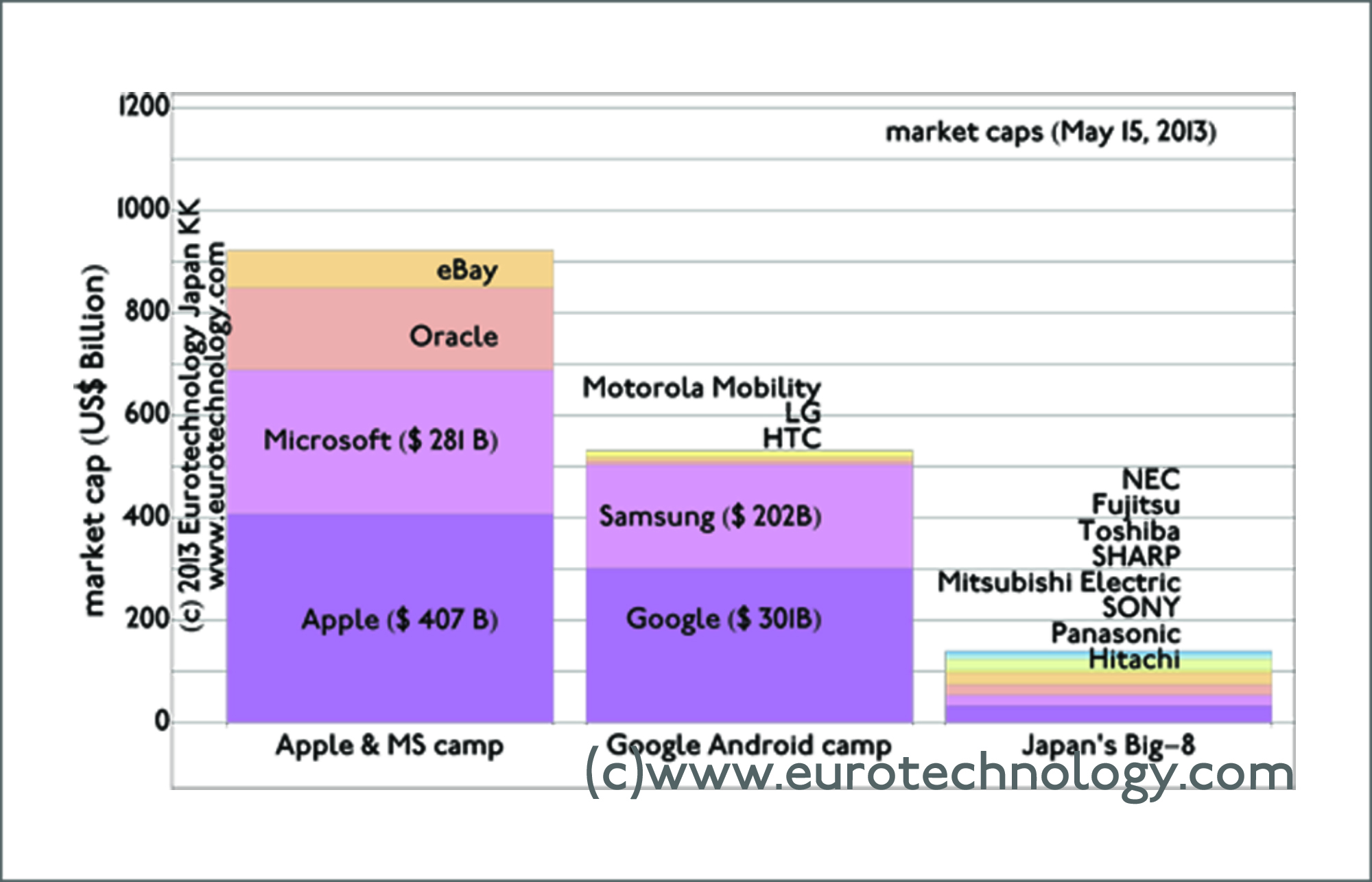

Japanese electronics groups need new business models (BBC-interview: Yen ‘not the cause of woes of Japan’s electronics firms’)

Japanese electronics groups combined as of similar size as the economy of the Netherlands Over the last 15 years combined annual sales growth was zero, and combined annual loss was US$ 0.6 billion/year Japan’s “Big-8” electrical groups (Hitachi, Panasonic, Sony, Mitsubishi-Electric, Sharp, Toshiba, Fujitsu, NEC) combined are of similar economic size as the Netherlands. Over…

-

Apple-Samsung Patent War and Impact on Japans Industries (talk at Foreign Correspondents Club Tokyo on Oct 2, 2012)

PROFESSIONAL LUNCHEON “Apple-Samsung Patent War and Impact on Japans Industries” Speaker: Gerhard Fasol Tuesday, October 2, 2012 12:00-13:30 Foreign Correspondents Club Japan (FCCJ), Yurakucho Outline: In a global war to dominate the smartphone market, Samsung and Apple have been at each other’s throats, playing out the war in courts around the world and accusing each…

-

SONY revival prospects and shareholder meeting (BBC interview)

SONY needs to leave 1990 structures behind and more more than commodities SONY revival from record YEN 455 billion loss for FY2010 SONY (6758) announced a record YEN 455 Billion (US$ 5.7 Billion) loss for financial year 2011, which ended March 31, 2012, and held the annual shareholder meeting on Wednesday. SONY revival: My points…

-

Taiwan’s Hon Hai Group invests in SHARP

Crunch time? – reviving Japan’s huge electrical/electronics sector SHARP fighting for survival SHARP (6753) last month forecast a record YEN 290 Billion (US$ 3.5 Billion) loss for this financial year – more than 1/2 of SHARP’s market cap, and SHARP’s new Sakai factory is reported to work at 1/2 capacity. Taiwan’s Hon Hai Group (which…

-

Japan’s tech companies need to restructure – CNBC March 27, 2012

https://www.cnbc.com/video/2012/03/27/japans-tech-companies-need-to-restructure.html Japan’s electronics industries – research report

-

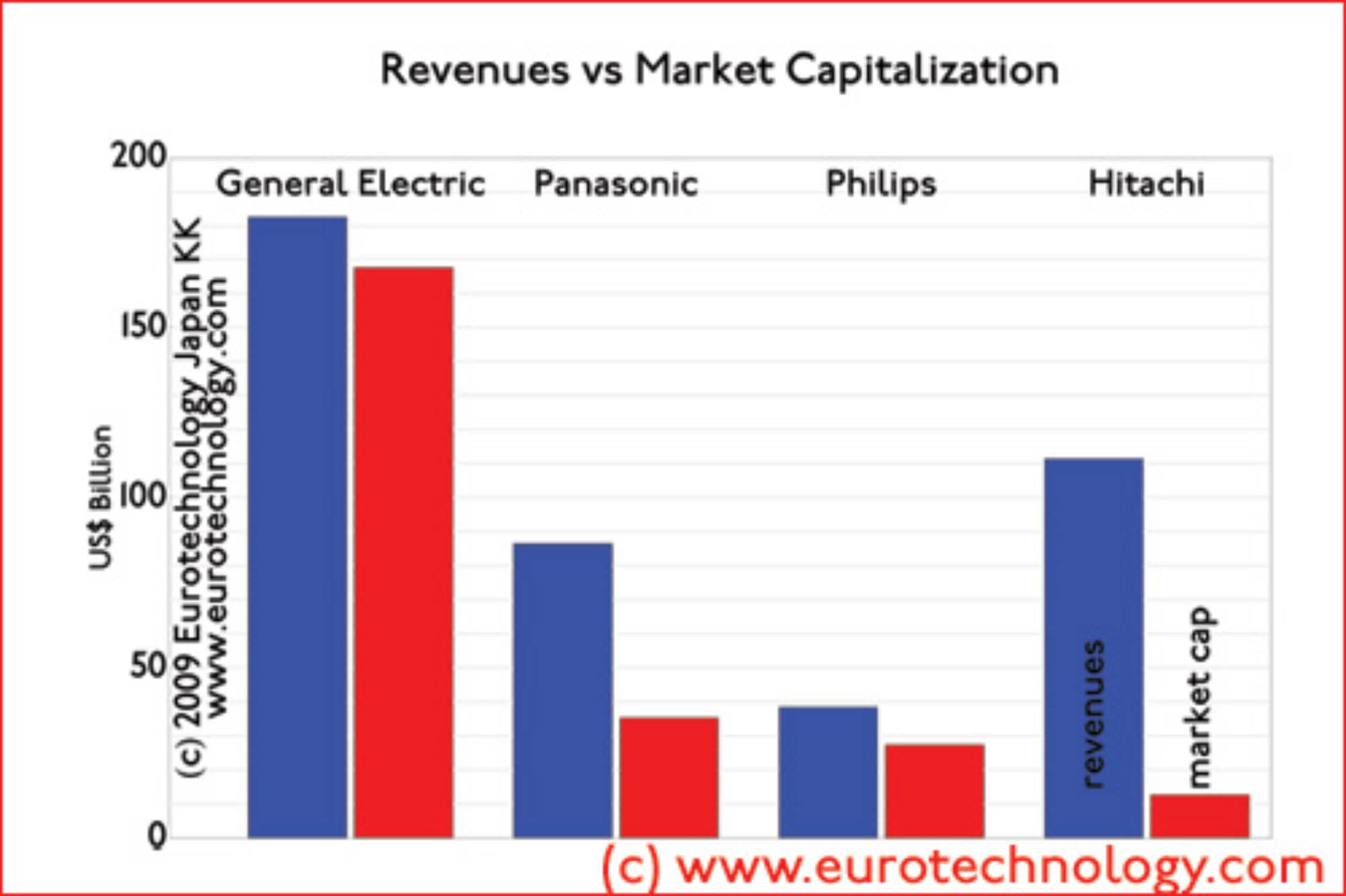

Japan’s Galapagos effect on market caps

Japan’s electronics giants market caps are remarkably low General Electric’s market cap is about 13 times higher that of Hitachi Some of Japan’s electrical corporations have remarkably low market capitalizations: General Electric has 1.6 x more sales than Hitachi, but has 13.3 x the market capitalization. Philips has 1/3 x Hitachi’s sales, but has 2.2…

-

Japan’s games sector overtakes electrical sector in income

Japan’s games sector is booming – and net annual income of Japan’s top 9 game companies combined has now overtaken the combined net income of all Japan’s top 19 electronics giants (including Hitachi, Panasonic, SONY, Fujitsu, Toshiba, SHARP… at the top, and ROHM, Omron… further down the ranking list). Why does it make sense to…

-

Japan electronics groups: global benchmarking

Japan electronics groups have far lower income/profits than EU or US comparable corporations Ripe for drastic reform and transformation: 18 years no growth and almost no profits Lets look at global benchmarking of Japan’s top electrical groups Panasonic and Hitachi (representative of Japan’s top ten electrical giants) – in our previous blog we suggested that…

-

Japan’s electronics companies & the crisis

Japan’s top 20 electronics companies combined are about as large as The Netherlands economically, and have big impact on the world economy. Our analysis shows how dramatically Japan’s electronics companies have been hit by the current crisis (except for Nintendo). We suggest that full recovery to 2008 (FY2007) levels may take until 2016 – about…

-

More Drastic Changes Needed at Sony (CNBC TV interview)

SONY needs drastic changes: from commodities to networks and communities More Drastic Changes Needed at Sony (CNBC Airtime: Thursday, May 14, 2009) Read more about SONY and Japan’s electrical industry sector Copyright (c) 2013 Eurotechnology Japan KK All Rights Reserved